Childhood Dream Expiration Date

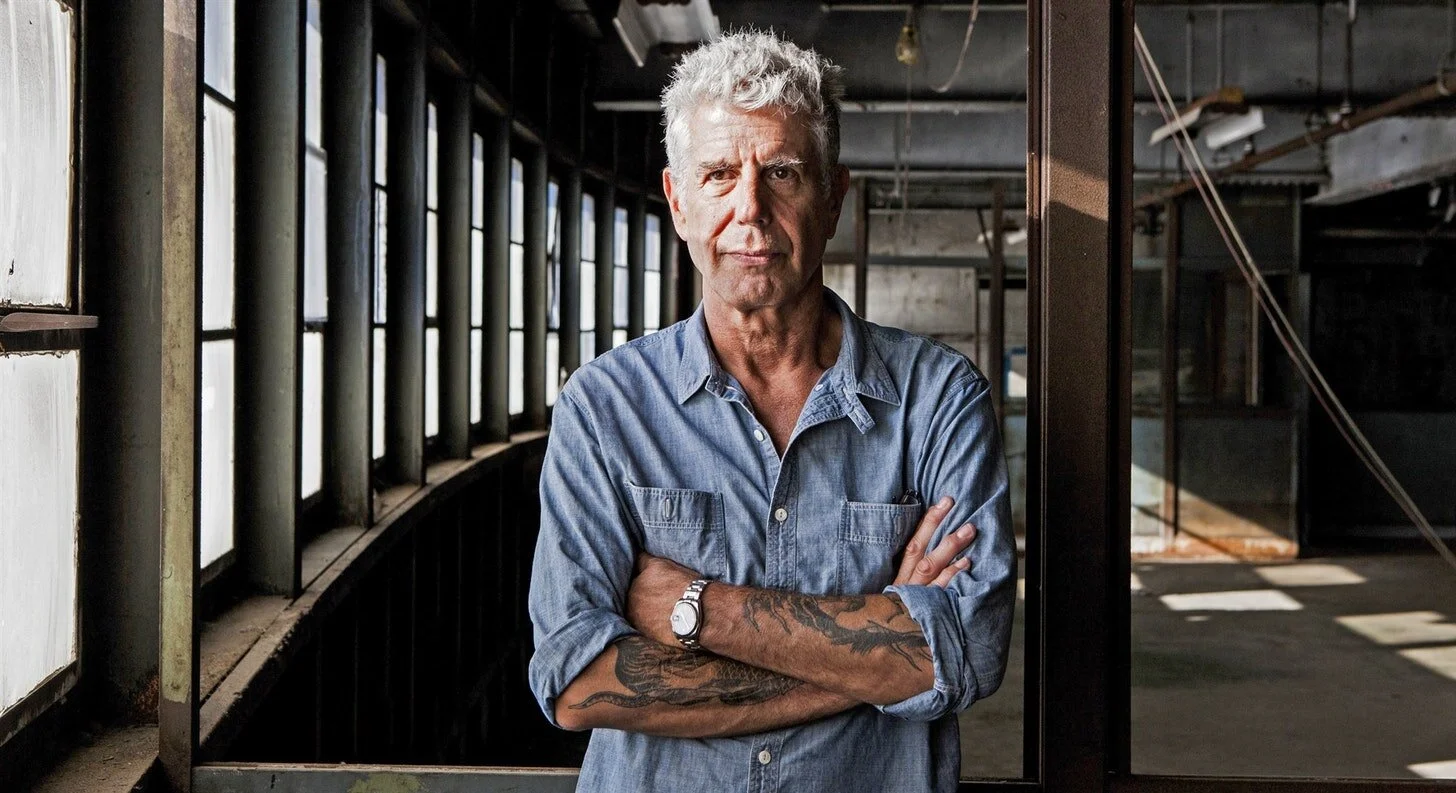

“When I visit a new city, I tend to eat my way through it,” he once said while sauntering through a dank alleyway in some far-off land. The camera cut from his shoes to a street vendor to a slow-motion shot of deep-fried pig’s tail entering his famous mouth. He took me from Tangier to Tokyo, arguably doing more to promote cross-cultural empathy than any other celebrity in my lifetime. I watched every episode of his show and felt like I lost a friend when he closed the curtains on himself.

When I was 18 years old, largely inspired by Anthony Bourdain, I created and hosted a YouTube show called Surfing For Change. With the support of my sponsor, Patagonia, I traveled to exotic coastal destinations, often alone or with a single cameraman, and covered environmental issues through the lens of surfing. Stories included plastic pollution in Indonesia, a proposed coal plant in a Chilean fishing town, and garment working conditions in Sri Lanka. Before each trip I watched Bourdain and attempted to copy his swagger and intonation, sure that if I kept at it I was destined to become—drum roll please—the Bourdain of surfing.

Unfortunately, when the camera was upon me, my mind would fracture between the line I was supposed to deliver and the famous TV personality I would one day become. My eyes would become shifty and toggle between the camera lens and my shoes like a jittery teen on a first date. I also failed to grasp that good TV is often the result of good writing, and Bourdain was a master. When he referenced heroes such as Joan Didion, George Orwell and Edgar Allan Poe, I thought he was talking about fellow chefs.

These adventures were great fun, but turned zero profit. So, in my mid-twenties, I attempted to level up and pitch my “Bourdain of surfing”concept to TV networks in Los Angeles. My pitch deck was peppered with buzzwords like “boots on the ground,” “young audience” and “immersive experience,” but none of my stories had any real thrust. I was also ruefully unaware that in Los Angeles, proclaiming that you are the Bourdain of anything is an overused meme, a laughable admission of naïveté.

Networks responded with an enthusiastic “Yes!” Then promptly stopped returning my calls. Later, someone told me that in this business there are only two answers: “Yes” and “Here’s a check.”

I grew up in a small beach town, and up until that point most of my travels had taken me to other small beach towns around the world, so spending extended stints in a big city was new and exciting for me. I learned that Los Angeles is not a single unified city, but many cities. Neighborhoods are separated by congealed traffic, so residents rarely drive across town if they can help it. If I’m in Santa Monica and you’re in Burbank, you may as well be in Burma. When the film industry first planted their flag in Los Angeles, a primary reason was the climate. Sunny days allowed for more filming without rain delay. Aesthetically, the city also appears to have been created by a filmmaker. Picturesque little scenes like the Hollywood sign, manicured palm trees in Beverly Hills, or the Venice canals work nicely for a camera angle. But if the camera zooms out from any of these individual scenes, it transforms into a sprawling cement jungle.

The topography just outside the city, however, is breathtaking. Malibu canyon has hiking trails, mountain lions and a meandering river. Over hundreds of years, the river brought with it sand and cobblestone rocks, which formed the shape of the seafloor outside the river mouth, creating the classic waves at Malibu. On the best swells, Malibu becomes a right-hand point break of velvety perfection.

While pitching my show I started attending networking parties where I schmoozed with people I believed could help sell my concept. I had a friend who was a member at Malibu SoHo House. Besides my friend, who was nice enough to repeatedly add me as his plus one and buy me drinks, I gathered that the criteria for membership was spiritual materialism. The men called you “brother” and spoke with plastified enthusiasm. The women were so physically beautiful it was as if they had peeled themselves off of a Victoria’s Secret catalog and walked into the party. With soft, faraway eyes, they often spoke about their recent ayahuasca journey, which transitioned perfectly into their new line of bathing suits, which were hand-made by women in the Peruvian jungle and smudged with Palo Santo.

The dress code was flummoxing. I would arrive one night wearing a T-shirt, shorts and flip-flops, attempting to look beachy and unbound. Much to my chagrin, everyone else would be in Louis Vuitton. Next time, I would arrive in slacks and a pressed button-up shirt. As luck would have it, derelict garb would be in vogue.

I was amazed to learn that everyone at Malibu SoHo House was a close collaborator with a celebrity, and together, they were on the verge of something big! I later found out that in this culture, lying is considered benign, and one's dietary choices are of much higher ethical concern.

I was not above it. I quickly found myself manipulating conversation to bring up my “brother” Kelly Slater, who I had interviewed precisely twice four years prior. Pro tip: When developing your sycophantic side, it’s important to refer to your famous friend on a first-name basis. If the victim of your mendacious word vomit doesn’t know who Kelly is, chuckle and pat their head.

SoHo House evoked social awkwardness that reminded me of high school. Suddenly, I had forgotten how to stand. Did I lean against the bar to look relaxed? Stand at attention with shoulders back to appear confident? Incessantly check my phone to signal my importance? I tended to amble around like a lost fawn, giving forced smiles to anyone who would make eye contact with me, then leave without saying goodbye, feeling enervated and hollow.

My older, actual brother, Toby, was never shy to give it to me straight. One day he told me, “People waste decades in LA waiting for other people to make their dreams happen.”

It was around this time that I began to loosen my grip on the idea of becoming the Bourdain of surfing. I knew that I wanted to tell stories for a living, but I realized that I now preferred podcasts over television.

Like many young men, The Joe Rogan Experience captivated my attention and exposed me to a range of perspectives, nuance and intelligent conversation that I couldn’t find elsewhere. The beauty of podcasting is the low barrier to entry. All it takes is a recorder and a couple of mics. Before I had time to talk myself out of the idea, I bought the equipment and started my own podcast with the painfully unoriginal name The Kyle Thiermann Show. Over the years, I had acquired a rolodex of professional surfers, journalists and outdoorsmen whom I could pester for interviews. I owe a great debt to Joe Rogan for creating a podcast that was driven solely by his own curiosity, thus giving me permission to interview anyone who would return my emails.

Asking questions, it turned out, came more naturally than staring into a lens while pretending to be an expert. I knew that my relationship with podcasting was true love when I had the insight that I would keep doing it even if my listenership was zero.

When I studied Rogan, I noticed that comedians and writers were consistently the most entertaining guests on his show. They spoke with a kind of clarity that cut through bullshit like a buzz saw. I decided that I should start having comedians and writers on my show, but I didn’t know any. One frequent guest on Rogan was a 57-year-old author named Chris Ryan who had written a bestseller called Sex At Dawn, a subversive big-idea book about human sexuality and our species’ predisposition to non-monogamy. Chris had an easygoing attitude, seemingly vast breadth of knowledge, and was one of my favorite guests on Joe Rogan. Chris also hosted his own podcast called Tangentially Speaking. So, I sent him an email, hoping to be a guest on his show, thus boosting my own podcast numbers. I’ll never forget his response:

“Normally when someone pitches themselves as a guest I assume they’re a self-indulgent dipshit and I delete the email. In your case, I’ll make an exception.”

I remember driving to the interview, anxiously rehearsing my answers to the questions I expected him to ask me. He asked none of them, but the podcast went well enough. Chris and I became friends and a new world opened to me. When it did, I learned a very important secret. That secret: There are two LA’s.

The first consists of people who are chasing success. The second, hidden just above it, is made of people who have already done what they came to LA to do. The ones in the latter category tend to be relaxed, downplay their accomplishments and show real interest in other people. They know that time is their most valuable resource and they protect it mercilessly. These people are often impossible to get in touch with unless you are introduced to them by someone they trust. Chris was now this friend. Suddenly, I was hanging out with writers and comedians and offering them surf lessons in exchange for an appearance on my podcast. I often felt intellectually inferior to these guests, but after our conversations my brain got bigger, and my podcast got better.

I started sleeping at Chris’ house up Old Topanga Road. More specifically, in his red Sprinter van, Scarlet Jo-van-son. Although his house was only a short drive away from Sunset Boulevard, which led into the heart of the city, Topanga reminded me more of the towns I knew in Northern California, like Bolinas or Mendocino. To get to Chris’ house I drove under a forested canopy, past horse stables and a wooden sign that read, “Slow Down, You’re in Topanga.”

Late into the night, our conversations would often turn comedic and subversive as he posed provocative thought experiments such as, “What do you believe to be true, but is too taboo to say out loud?” I think I responded, “The Grateful Dead kinda sucks.” Chris is an iconoclast, philosopher and self-proclaimed “dude in hammock.” He lived in Spain for nearly 20 years, and often laments that Americans overvalued grit and undervalued flexibility. He could have easily built an empire, but decided instead to host a podcast and go camping in his Sprinter van, because that’s what he loves to do. Between sips of Sierra Nevada Pale Ale he would often blurt out truths so profound my head would spin for a week, then he’d forget what he had said, and excitedly change the subject to his new solar-powered camping light.

One night, I told Chris about my former dream of becoming the Bourdain of surfing, and how now, writing and podcasting felt more important to me. He took a sip of beer, sighed, and said, “Childhood dreams are the dreams of children.”